Immersion and UBD

Recently our teacher study group gathered to initiate a year long study on the Understanding by Design framework. I listened closely and everyone agreed on having clear outcomes in mind according to our standards based curriculum. But where I couldn’t find consensus was on what happens next, how from the unit opening students propel toward the application and transference Wiggins talks about. For some it was to write essential questions, plan summative and formative assessments, and plan activities accordingly. For others it was picking content carefully, letting students unlock the artifacts for themselves, each class taking a slightly different route, as the teacher guides their trajectory. Grant Wiggins clarifies,

“I’m talking about being so prepared that you hear a student comment as a fantastic entry point to go where we want to end up.”

But he goes on to place “critical and creative thinking” at the core of how we want students to interact with content. The Harvard Business Review echoes,

"All too frequently, we hear managers complain that their employees don’t think for themselves. Yet these same managers punish their subordinates for failing to follow instructions.”

Are we instructing students into learning trajectories by merely posting essential questions and projecting them into a learning rubric before giving them a chance to connect their own spontaneous learning experiences with content? How might we motivate students intrinsically to manage their own learning trajectories?

I believe the key is in the careful choice of content, and just as Wiggins asked of teachers to immerse in content, immersing students so thoroughly that they own the framing of their learning narrative.

Honing the teacher’s lens on the private sector, this is branded as…

“...job crafting — that is, having the ability to reshape one’s actual work — this can lead to improved performance and happiness. By giving employees the right to be themselves, even within the bounds set by the organization, firms can better engage their workers."

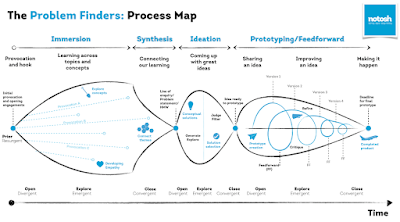

In the classroom, allowing students to “be themselves” is listening deeply during the immersion process. How do they react to the content, what kind of wondering comes out of contact with the artifacts? Allowing for that space validates what poet Kevin Brophy called “the messiness of thinking”. Ewan McIntosh of NoTosh calls this “divergent thinking”, opening the mind to wander around all the infinitesimal routes learning can take, allowing what Roger Martin teaches as the design thinking advantage, the integration of analytics and intuition. Flaring student attention toward all the possibilities incites wonder, and out of that wonder a gravitation toward strong feelings and associations to spontaneous experience and prior formal learning. Isn’t the exposure to this wonder why we all went into teaching?

One primary misconception of teaching and learning is that it is a cognitive experience devoid of aesthetic, ethical, affective connections. Perhaps this is Blooms misunderstood, an over emphasis on the cognitive domain, neglecting the affective domain, and the never finished psychomotor domain - although Agency by Design and other drivers of the modern Maker Movement are rounding out how knowledge is defined and constructed.

The Carnegie Foundation cites one critical factor of motivation to be…

“...a student’s belief that he is able to do the work, a sense of control over the work, an understanding of the value of the work, and an appreciation for how he and the work relate to a social group.”

Combining the sense of wonder together with the learning community is the beginning of the collaborative work mindsets students would need to reach common goals throughout the project.

The Launch

In the immersion process into this study of indigenous cultures changing over time, we attempt to capture the affective, ethical, aesthetic connection to learning from the outset. We try to contextualize content in the mechanics of alternative reality gamification, and allow students time and space to create a personalized learning experience based on campfire (whole group), watering hole (small group), and cave (self-encapsulation time), in order for students to apply their knowledge into real life experiences.

It began with a normal classroom activity, sorting vocabulary words, so students had every reason to expect that this unit of study would follow like every other. But the second day we pretended to be having technical difficulties at the computer, again nothing out of the ordinary - “What’s this that keeps popping up on my screen…?”

In this hero’s journey students spent the next day in a rotation of activities in the library with a specific purpose - find the artifacts, collect the artifacts in post-it sketches, and build the alter to level up and “unlock” their gods’ names. Rotations consisted of learning the digital routes to their web quest, finding and exploring the books and other resources, learning the best key word combinations for artifact image searches, a making of the alter, and a see-think-wonder routine.

The design of the see-think-wonder routine was to allow four to five students small group time with a teacher for ten to twelve minutes collecting thinking around a specific goal - focus on one artifact, connect prior knowledge, and begin an inquiry into their study of Native American peoples.

Why artifact?

Objects embed knowledge and provide a focal point for group discussion. Through close observation, by listening to multiple viewpoints, each voice reacts by building or contesting those before. This small group work trains students for collaborative thinking, for using collective intelligence to pool their disseminated knowledge into a co-created construction. This is based on Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory of learning and the Leont'ev branch of Activity Theory in which tool or artifact serves as catalyst for individual and group cognition. This “tool” can be methods for group interaction, physical and digital tools, a content piece, and the learning space itself.

The see-think-wonder routine provides the rules of engagement. The context of the small group allows for rapid socratic dialogue, and because the objective is to get all heads around the artifact interacting verbally with the teacher jotting notes. This low threshold entry ensures that every student engages. STW changes the rules of the normal KWL prompt (what I know, what I want to know, what I learned) in that it lessens the pressure of feeling probed. By working with peers and an adult, a more inviting zone of proximal development is reached, enabling students to build off of each other’s input, guided by the adult’s socratic dialogue.

collaborative building in interactive media space #learningspaces #edchat #makered #aassa #newlit #alclassroom pic.twitter.com/S57cJZRgtS— Chris Davis (@chrisdaviscng) May 10, 2016

See-Think-Wonder

In the “see”, students may not interpret, there is no knowing, there is only observing that which is readily evident if you look sharply. Students’ eyes project inward to describe. I guided them carefully to “tell me more about that” or “can you zoom in more and pick it apart” kinds of interaction.

The “thinking”, again changes the language of “knowing” in that nothing is really definite, there is only what one thinks. The scale slides from what is incontestably evident to what is open to multiple interpretations. Really all of this is priming the mind for the areas of not knowing. I’m not clear on the psychological mechanics of this but in the few times I’ve applied this routine, students really open up in the wonder stage, which in this activity was only given about two minutes.

The “wonder” brings the true richness. Unlike the “what I want to know” of a KWL, students have front loaded their cognition with the “see” and “think”. Ideally we would have used real physical artifacts, samples of video, music clips, and whatever would create a sensory experience, but for our purposes here we used photographs. Students were pushed to wonder as wildly as possible, to cast a wide net, and to encourage what Freire considered to be the root of learning, the critical discussion. The more divergent wonderings we can validate, the more likely students will jump in and debate each other.

Many People Few Ideas

While I was thinking about the specific topics we wanted students to investigate - environment, religion, daily life, roles of society, and commerce - I went with the trust in the connectivity of all things, and from my own anecdotal experience, nine times out of ten, students drive their own inquiry in the intended direction. With artifacts as guiding points for inquiry our thoughts tend to overlay. Kundera encapsulates this well in separating feeling from thought...

"I feel therefore I am... ...applies to everything that's alive. My self does not differ substantially from yours in terms of its thought. Many people, few ideas: we all think more or less the same, and we exchange, borrow, steal thoughts from one another. However, when someone steps on my foot, only I feel the pain."

What “we know” is often what “we think” and what “we think” is often based on opinion which is based on what “we feel”. The wild feelings are where students are creating the critical affective, aesthetic, and ethical connections to their learning. Developing feeling for content is not only creating attachment and meaning, it is validating the most primal component of identity, emotion. And if I’m not making myself very clear in this roundabout thinking, then let me reiterate in bold print.

Student agency of framing learning and and building a sense of ownership does not happen merely by having the teacher do all the divergent thinking and establishing the essential question on the board for the students to ponder.

Essential Questions are explicit UBD steps to planning, but in the launching of new units of study, students must immerse and experience wonder, individually and in group. There will undoubtable be messiness, topics surface that we simply cannot expose fifth graders to, but allowing for this wide net of inquiry will ensure a greater sense of ownership by students.

Engaging with Fantasy Drama

The next day students gathered in our Media Innovation Studio and pitched their alters to the class in an attempt to awaken the gods. There was the expected fifth grade giggling but more surprising was the seriousness of some of the invocations. Two years earlier I remembered one student was the ring leader of dramatic acts during recess in our sandbox. A group of girls would spend their entire recess developing elaborate choreography in a charades-like play. She now resourced her talent of role-play before the class. And then, the gods revisited (“Oh, what is this on my screen?") guiding students toward the Avatar Challenge, and the inquiry process of what they would have to learn before creating their avatars. One student was quick to connect the Percy Jackson series, “They are possessed, like in Percy Jackson, the gods are using the teachers as a medium of communication!” Another likened it to Harry Potter speaking Parseltongue.

Revisiting the See-Think-Wonder routine from the day before students were asked what else they would have to learn about their Avatar’s world before “stepping into their avatar’s skin and see through his or her eyes.” As a class we created affinity groupings, common threads in their questions. The groupings, with a little teacher guidance formed a list of “critical questions” authentically generated by students. We discussed how we needed a guiding “essential question” for each group that would guide them through their Avatar construction.

“How might we see through our Avatar’s eyes to understand how he or she survived in his or her environment?”

“How might we understand our Avatar’s religious beliefs by walking in his or her skin?"

Now students seemed ready to begin their research. This was the first attempt at these alternative reality gamification methods. I wasn’t sure how students (and teachers) would respond, but students captured the sense of narrative, the removal of ego by seeing through an Avatar’s eyes, and the Design Thinking elements that we hope will drive them to explore artifacts as design solutions, and develop empathy for indigenous peoples through their own personal lens into their Avatar’s history.

Below:

examples of teacher notes from the see-think-wonder routines.

examples of teacher notes from the see-think-wonder routines.

In future posts:

gamification mechanics, the design challenge of artifacts, writing historical narratives

gamification mechanics, the design challenge of artifacts, writing historical narratives

Inca

I see...

…there are many tubes, thirteen to be exact.

…it is made of wood.

…some tubes are larger than others, shorter on the left and getting bigger to the right.

…the tubes behind are a little bigger than those in front.

…it has a black, think, string.

…it has a hand made decorative strip, red and blue, with white patterns.

…there is a red strip with three spaces and squares with two X’s.

I think...

…you blow on it to make sound.

…it makes a calm sound.

…the longer and shorter tubes make different notes. The longer ones have a lower sound, the shorter ones have a higher sound.

…it is similar to a recorder.

…the mouth moves back and forth to make the notes.

…there is more space for air on the longer tubes to make lower notes.

I wonder…

…why where are two rows.

…why it’s made of wood and not metal.

…why more space makes a lower sound.

…why it has so many decorations.

…if the sting is for hanging or for decoration.

…what other instruments they played.

…where they find the sticks in their environment.

…if there are different sized instruments.

…how they created the colors for the decoration? What flowers and plants.

…if they only played music or did they dance and sing too.

…what they sang… what they danced.

…if it was used for festivals.

…if they liked a wind instrument because of their environment (there is a lot of wind in the Andes).

Iroquois

I see…

…there are lines all over his face.

…the mouth is big, open, and comes out of its face.

…a tooth.

…round eyes, reflective.

…triangular nose, really big.

…geometric shapes, eyes-circles, nose-triangular, mouth-rectangular or oval. The head is oval.

…red with dust in the lines.

…wood or clay.

…real human hair.

I think…

…this scared opponents.

…scared little kids to behave.

…represents a god or a demon.

…a special person wore this for a celebration.

…this god protected them and helped them - war, food, shelter, water.

…the mask is part of the god and part of a dance - all part of their worship.

I wonder…

…where the hair came from, a horse’s tail or a human head.

…if the red color came from rose petals, berries, or blood.

…how they made perfect circles.

…why it is scary? Who are they scaring?

…who got to wear the mask?

…what did this mean to children?

Aztec

I see…

…arrows, white feathers.

…the arrow connects to the bow shaped wood thing.

…lines in the wood.

…rope where the hand goes.

…the red part of the arrow goes in to a hole.

I think…

…the rope is for friction so it has a firmer hold, it grips better.

…the feathers are for not going off track, more speed and thrust.

…it is a weapon to catch enemies, for war, and for food.

I wonder…

…why the feather makes it go faster.

…how it projects the arrow.

…who hunted, how did they organize.

Algonquin

I see…

…a brown wigwam.

…tree bark makes the walls.

…sticks make the structure.

…sticks are outside and inside.

…sticks are bound and tied together with vines.

…it is a half sphere.

…a circle of stones for a fire.

I think…

…the stones are for hammering the wigwam vines into rocks so it won’t fly away.

…they use tree sap so the bark sticks.

…there was fire inside and outside for light and heat.

…tribes made villages and lived together.

I wonder…

…how long they stayed in a wigwam.

…did they live together or alone.

…how many lived in one wigwam.

…if they were nomads.

…how they wigwam changed and improved over time.

…how these houses kept them alive for 8000 years.

…did the bark get saturated and drip and leak.

…could they make fires inside.

…if it is better getting wet or burning your house down.

…if the materials show us they were not nomadic.

Pueblo

I see…

…leaf shaped drawings around the rim, six of them.

…the vase is almost heart shaped.

…geometric shapes, hexagon, triangle, circle, ovals, pentagon.

…made of clay, orangish colors.

…painted lines.

I think…

…It’s clay, crafted from the environment.

…used clay because it is easy to mold, the fire keeps its shape - like Playdo at first, then had after heating.

…it is a flower vase, a water vase, for fruits.

…used for carrying water.

I wonder…

…what they kept in this vase.

…if it kept corn.

…is it just decoration or is there a bigger meaning.

References

Agency by design. (2015). MAKER-CENTERED LEARNING AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF SELF: PRELIMINARY FINDINGS OF THE AGENCY. Retrieved September 26, 2015, from http://www.agencybydesign.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Maker-Centered-Learning-and-the-Development-of-Self_AbD_Jan-2015.pdf

An Example of PBL in Early Elementary: How I Started. (n.d.). Retrieved September 26, 2015, from http://www.edutopia.org/discussion/example-pbl-early-elementary-how-i-started?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=092315

Atkins, K. (n.d.). Inquiry-Based Learning: Developing Student-Driven Questions. Retrieved September 27, 2015, from http://www.edutopia.org/practice/wildwood-inquiry-based-learning-developing-student-driven-questions?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=092315

Davis, C. (2013, May 28). Kevin Brophy Interview with Third Graders. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from https://youtu.be/f0tJfLLXzow

Davis, C. (2015, July 1). Voices at ISTE 2015: Paul Darvasi on Pervasive Learning. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5GgdrZanpNo

Davis, C., Peterson, N., Olsen, E., Hobson, R., Barrera, L., & Thies, R. (2015, September 8). The Call to Action. Retrieved September 27, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c2edkTRGiFs

Davis, C., Peterson, N., Olsen, E., & Hobson, R. (2015, September 8). The Call to Create an Avatar. Retrieved September 27, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aEc__4iZzqc

Davis, C., Nino, R., & Lopez, D. (2015, September 16). The Call to Create Natural Pigments. Retrieved September 27, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vCSA7y8eAok

Gee, J. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gino, F., & Staats, B. (2015, June 3). Developing Employees Who Think for Themselves. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from https://hbr.org/2015/06/developing-employees-who-think-for-themselves

Headden, S., & McKay, S. (2015, July 1). MOTIVATION MATTERS: HOW NEW RESEARCH CAN HELP TEACHERS BOOST STUDENT ENGAGEMENT. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from http://cdn.carnegiefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Motivation_Matters_July-2015.pdf

Krechevsky, M., & Stork, J. (2000). Challenging Education Assumptions: Lessons from and Italian - American Collaboration. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(1), 57-74. Retrieved September 27, 2015, from http://www.makinglearningvisibleresources.org/uploads/3/4/1/9/3419723/krechevskystorked.assumptions.pdf

Kundera, M. (1991). Immortality. New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

Martin, R. (2010, November 10). Rotman Dean Roger Martin on Design Thinking. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-ySKaZJ_dU&feature=youtu.be

McGonigal, J. (2011). The Benefits of Alternative Realities. In Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York, New York: Penguin Press.

McIntosh, E. (2011, November 18). TEDxLondon - Ewan McIntosh. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JUnhyyw8_kY

My PBL Failure: 4 Tips for Planning Successful PBL. (n.d.). Retrieved September 26, 2015, from http://www.edutopia.org/blog/pbl-failure-planning-successful-pbl-katie-spear?utm_source=SilverpopMailing&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=092315

Pike, M. (2015, September 20). "Our opinions aren't opinions; they are emotions that feel like opinions." @RyanHoliday #TrustMeImLying #dare2design #dtk12chat. Retrieved September 26, 2015, from https://twitter.com/mosspike/status/645809099611877376

Ritchhart, R., & Church, M. (2011). Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Thornburg, D. (2007, October 1). Campfires in Cyberspace: Primordial Metaphors for Learning in the 21st Century. Retrieved September 28, 2015, from http://tcpd.org/Thornburg/Handouts/Campfires.pdf

Weintraub, P. (2015, May 12). The Voice of Reason. Retrieved September 25, 2015, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/201505/the-voice-reason