Enacting the Visible

The camera was once considered a technological curiosity capable of mirroring the world. Popular demand for portrait photography mimicked portrait painting, the capture of the idea of the person, shadows in Plato’s allegory of the cave. Placement of camera tripods was very similar to painting easels of the period. During Photography’s Golden Age, the photograph became expressive form. Interpreting images meant engineering through the camera lens, the screen, into the other side of the viewfinder to reveal the perspective and ideas of the photographer.

Two photographers worked from everyday objects in their environment as an attempt to slow the fleeting shadows of the sensory world and reveal the unique beauty of the commonplace fork, plate, pepper, and light play. Andre Kertesz photographed “from above” and positioned the camera in obscure angles. He often photographed the commonplace, the every day object, the intersection of light and people moving across the plaza as seen from his window. Edward Weston similarly isolated objects, giving new meaning to the mundane. To achieve the depth of field in his pepper photographs, he had to use a pin hole aperture, taking four hours for an exposure. Stare at one of his peppers for two minutes and the mind “enacts” motion, human forms, dance, or a complete loss of perception of a physical object, like the realm of Rothko’s paintings.

|

|

André Kertész

|

|

| Edward Weston |

Technological advancements have repeatedly served as metaphors for the brain and body function - steam and pressure tubes, electric pulses, radio signals, computer processors, the hive mind of the internet. There is a kind of reflective logic that what we create in the world becomes metaphor for how we think of our own processing, a kind of “you are what you do”, or “make”. McLuhan went as far to say, “We shape our tools, then our tools shape us”. Wilson Miner takes this a step further with the example of the car, which has changed very relatively little, but we have created an entire world around it, allowing it to determine how we design cities, how we interact and behave.

I would argue that is only true of the passive user of a tool. In the case of children, the tools we put into their hands throughout the last century show us how our whole concept of childhood, of what children are capable of, of how humans develop, changes in the interplay between culture and technology.

These ideas were churning around as I recorded a podcast with Hectalina Donado where she repeatedly the idea that child learning space is something we as adults design.

Childhood as Construct

“Children are human beings, they want to learn, they want to understand their world.” - H. Donado

A few years ago the MOMA hosted the Century of the Child exhibit, taking the name from progressive Swedish educator Ellen Key, who published a book of the same name in 1900. At the beginning of the 20th century Key wrote…

"At every step the child should be allowed to meet the real experience of life; the thorns should never be plucked from his roses."

Ellen Key's ideas influenced progressive education movements around the world including Maria Montessori, an Italian predecessor to the Reggio Emilia approach. Hectalina Donado pioneered the approach in Barranquilla. During our podcast she said...

“Childhood is not just fun and games, a time where we are waiting to be a grownup when we start doing serious things.”

The seriousness of childhood can be decoded by what adults believe are the "things" children should interact with. The MOMA exhibit curates these objects designed for children throughout the 20th century. Even earlier, Pre-Lock/Rousseau, children were viewed as incomplete adults. Lock’s tabula rasa approach began this idea that children are equal, very much a reaction to attitudes of divine providence of the noble class. Rousseau viewed childhood as a constructivist period of innocence and play. Children were noble savages uncorrupted by the rules of society. Since then childhood has been a malleable cultural construction.

The artifacts in the MOMA exhibit reflect how adults have idealized childhood.

|

| Frobel's Gifts |

|

| Dewey's Laboratory |

|

| Montessori's Geometric Shapes |

|

| Steiner Thought as Energy |

|

| Balla, Italian Futurism, speed and industry |

|

| Bauhaus, mass produced, multipurpose |

|

| Bauhaus aesthetics and color |

|

| New York City children's gardens |

|

| Sugata Mitra Hole in the Wall |

|

| Lego interchangeable pieces |

|

| Seymour Papert Logo Turtle (not part of the MOMA exhibit) |

The artifacts we surround children with reflect this constantly changing belief of childhood and learning. The tools within Reggio Emilia spaces such as Hecatlina’s EXCEL most often have “tools” in two forms, those of construction, and those of “hanging inquiry”, artifacts similar to Froebel’s gifts, embedded with knowledge waiting to be unlocked by the children. Such learning spaces curate their tools and content artifacts in this ideal space for children. However, it is important to realize that cultural mythologies can lay dormant and resurface in new signs. Market forces long ago honed in on the manipulation of children, and the idea of childhood, and filled it with "fun and games" that treat the child as passive consumer. Our over-accessorized childhoods can continue to promote ideas of children as miniature adults and entrench gender stereotypes, or reinvent them in new form. Excluded from the MOMA's curation from MOMA’s is the larger Kinderculture of Barbies and Bratz teaching girls that “Math class is tough” or carrying dieting books titled “Don’t Eat”.

|

| Baby-sitter Barbie 1963 |

|

| Bratz 2018 |

“Homo Americanus”, how blue was reassigned to boys, color and object as extension of self identity in the early years, #kinderculture, decoding our prefabricated worldshttps://t.co/5OyyrR8GVU #medialiteracy #earlychildhood #makerEd #edchat #k12 #literacy #pink #blue pic.twitter.com/DPecIXmpZH— Chris Davis (@chrisdaviscng) April 16, 2019

Media and Children

“Our image of the child is one of being powerful, we don’t bombard them with exterior images from movies.” - Hectalina

Scroll back to 2008 and we were giddy with the potential affordances of our digital technologies, the collaborative, metacognitive, multimodal, and mindful applications seemed so... visible, tangible in these new tablets and phones. Dewey wrote about learning experiences as "potential future selves". My first look at the iPad and I saw nothing but a passive instrument, a clever mobile TV screen to capture even more of our attention. Then seeing it in the hands of groups of children, beyond the multimodality of capturing thought, it was the collaborative way they constructed around the tool that gave me a glimpse of our potential learning design.

Leveraging #collaboration with one device - the rap challenge #garageband #hiphopEd #edchat #dtk12chat #edtechchat pic.twitter.com/f58XnYcZYa— CNG Elementary Tech (@elemprojects) January 29, 2016

But look around in public spaces today and what is overwhelmingly evident is the dumbing and numbing effect of our digital technologies, how a populace has fallen for The Idea of Progress and been duped into being mined for data, scrolling through the attention economy’s treadmill. It is 2019, Facebook markets to kids, Youtube fails to channel appropriate materials toward primary age, online Ed is about to target pre-schoolers, and trolls are live streaming with tweens on Tik Tok. Note that Bytedance, the owner of Tik Tok recently settled for $5.7 million for mining data and collecting personal information from kids under 13 without parent consent. Last August Bytedance was valued at 75 billion. They continue.

The pressure shifts for schools to not just create an ideal protected space for young constructivists, but to teach the intelligent uses of our technologies. Digital/Media literacy efforts should not just be reactionary, but should lead with examples of smart technologies and defense tactics against the dark arts of media embedded with emotional manipulation. That means bridging our notion of “technology” between old and new literacies, creating the culture around the tech, not succumbing to lowest common denominator Pavlovian responses to three magnetic aspects of new technologies - interactivity, multimodality, and powerful narrative.

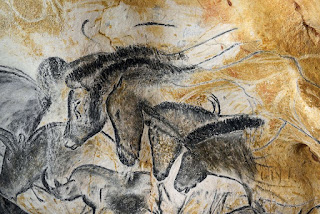

Storytelling has not always been text based interaction, it has deeper roots as transmedia, participatory event. Thirty-thousand years ago the great hunts portrayed on French cave walls of Chauvet depict motion similar to futurist painting. Storytellers would have been illuminated by torch lights, their shadows most likely dancing on the walls. These story arenas were by design in naturally made acoustic echo chambers. I imagine these were not solemn sit and listen events, the call and response participation must have been raucous. And this is how our students should experience language and narrative, with space for quiet, mindful construction of writings which are then brought to cavernous, carnivalized “campfires”. Our digital technologies bring back this multimodality of narrative. The insistence that language development in narrative is only done alone, silently, is ignorant of pre-Gutenberg orality and non-linguistic forms of expression, the traditional backbone of literacy. Our default experience with multimodal storytelling has been overshadowed by the goals of the entertainment industry.

Hectalina explained…

“…no Micky Mouse, that is Hollywood’s idea of what a child likes. We take these children seriously.”

Childhood’s constant construction can be a challenge. In Hectalina’s adopted Barranquilla, for example, children are often celebrated, dressed up, put on stage, and showered with whatever makes them visibly happy. This can lead to incredible advantages for learning with children having little inhibition as participants in events, but can be a challenge in communicating the invisible aspects of learning.

The Invisible Etherial

“I can't quite tell which of my thoughts come from me and which from my books, but that's how I've stayed attuned to myself and the world around me for the past thirty-five years. Because when I read, I don't really read; I pop a beautiful sentence into my mouth and suck it like a fruit drop, or I sip it like a liqueur until the thought dissolves in me like alcohol, infusing brain and heart and coursing on through the veins to the root of each blood vessel.”

Bhumil Hrabal, voice of Hanta, Too Loud a Solitude

Hanta’s realization is that he has condensed the whole of books into a few segments and ideas he connected with, like new branches to the trunk of his schemata. Shiela Heen similarly notes that through all the programs we watch, books and articles we read, that when it comes to conversing with friends about them, it boils down to a sentence or two, often masking the real depth of why we spend so much time pursuing knowledge, the nature of our informavore selves. Pragmatists like Dewey would say we have missed the Why of learning, knowledge is not something we fill our head with, rather it is action upon the world, that the pursuit of information is incomplete until it better informs action.

I have been in school pretty much my whole life, as student, as teacher, coordinator, etc. And both Hrabal and Heen communicate the problem of the “distillation” process of “schooling”. The primary focus is on What and How to teach and learn with a minimum of attention to Why we teach and learn. Sylvia Martinez reflects that the biggest challenge in working with schools is that teachers have no theory of knowledge, most have not engaged with the Why. The “visible” which is often the most easily metricked presides over the “invisible” not so easily quantified aspects of learning.

I have been in school pretty much my whole life, as student, as teacher, coordinator, etc. And both Hrabal and Heen communicate the problem of the “distillation” process of “schooling”. The primary focus is on What and How to teach and learn with a minimum of attention to Why we teach and learn. Sylvia Martinez reflects that the biggest challenge in working with schools is that teachers have no theory of knowledge, most have not engaged with the Why. The “visible” which is often the most easily metricked presides over the “invisible” not so easily quantified aspects of learning.

"When a flash of lightning illumines a dark landscape, there is a momentary recognition of objects. But the recognition is not itself a mere point in time. It is the focal culmination of long, slow processes of maturation. It is the manifestation of the continuity of an ordered temporal experience in a sudden discrete instant of climax."

John Dewey, The Live Creature and "Etherial Things"

Vygotsky 80 Proof

In these visual distillations of Vygostsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, the depth of his ideas are lost. Vygotsky considered multiple variables in a learning environment simultaneously (much like this blogpost). Tools extend potential learning objectives. Tools are multiple factors within a complex learning system. Tools can be invisible, and what is correlated can be confused for causal. CHAT (cultural historical activity theory) extend Vygostky’s idea to incorporate cultural rules, division of labor, community of the learning process and product.

Perhaps, Hectalina distills this more clearly…

“Go beyond what you see, bring the invisible out.”

Sometimes this means suspending our own cultural beliefs on childhood, and creating the tools and environment for child construction to happen. Culture may prioritize language, particularly in the representational form of text, but children are decoding a world around them, most of it non-linguistic, much of it invisible.

CMYK and RGB

Like the first hundred years of photography, where photograph was considered reflective mirror of reality, our tools of learning have a way of congealing, of dictating a culture of learning. Our re-appropriation of those tools give us back the leverage in the formation of a culture around them. This is their catalytic potential, to soften the molds, re-awaken a malleability in childhood and learning.

For example, Reggio Emilia, like many Steiner schools, rejected technology, constructions were to be from “natural” materials. Lately, color slides and light tables, and projections have become part of the constructivist toolkit, reflecting a shift in acceptance of digital technologies. Children continue to work with paints learning the subtractive properties of CMYK (mixing all colors makes black), but also play and learn with additive properties of RGB (mixing all colors makes white). This marks a shift in cultural attitudes toward the tools of construction and need to differentiate between creative and passive tech.

Science or Selfie

Susan Sontag described tourists who, unsure of how to interact with a strange environment, separated themselves from it, “shooting” pictures, capturing images. Photography affords Art, and Art affords Science, if the tool is used to enact an idea upon the environment in the pursuit of the solution to a problem. Everyone is now a photographer, the technology is right there in the palm of your hand. It all depends on what you do with it - narrate a story, simulate an experience, make the viewer feel an interactive part of it, test an idea... - or recede into a moment of narcissistic solipsism. Sontag saw it coming...

"The camera makes everyone a tourist in other people's reality, and eventually in one's own."

My inadvertent “enactivist” theory of childhood coincides with this catalytic change, and it builds upon a long tradition of constructivist theories of knowledge. Philosopher and brother Bret Davis explains that as we grow we increasingly appropriate "technologies" in our environment, leveraging them toward our life goals. Teaching has always seemed like an art of collective agency. Maybe that will turn out to be our greatest technology. I believe it is the distinct role of educators, learning communities, researchers, philosophers, artists, etc. to define the tools of our learning spaces, design the experiences within, separate technologies of constructivism from technologies of consumerism, and enact the visible from the invisible. We define the tools and we create the culture around them. We are the designers.

“We are a product of our world, and our world is made of things.”

Galveston at Dawn

Our digital technologies are often associated with speed, algorithms performing in a microsecond what would take human processing long periods of time. When I switched from analogue to digital photography I lost some of the slowness of producing images, the meditative feeling of watching developer wave over paper as I rocked the tray. It was only later that I realized that I was reacting to, becoming a mirror of digital tools instead of creating the world around the technology.

On a recent visit to my hometown, Galveston, I took a series of long exposures with a tripod. Before sunrise the surf raged and raced up the shoreline making it disorienting and difficult to walk. Some exposures were as long as two minutes. The resulting series is calm, serene, scenes between worlds of mind and experience. They serve as a reminder that, as disruptive to mindfulness as our technologies have become, we create the experience. For learning spaces that means moving from episodic activties toward the longer goals of “events”.

References

Boone, J. (2014, November 24). The 14 Most Controversial Barbies Ever. Retrieved from https://www.etonline.com/news/154308_the_14_most_controversial_barbies_ever

Build Design Festival. (2012). Wilson Miner - When We Build. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/34017777

Davis, C. (2013, May 10). The iPad, Media Production, and Shared Learning in Elementary. Retrieved from https://celebratecng.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-ipad-media-production-and-shared.html

Davis, C. (2019). Hectalina Donado on Childhood and Constructivism. Retrieved from https://soundcloud.com/chris-davis-276158228/hectalina-donado-on-childhood-and-constructivism?in=chris-davis-276158228/sets/journeys-in-podcasting-1

Davis, C. (2017, September 5). On Slowness: The Sense8 Potentials of Instagram. Retrieved from https://celebratecng.blogspot.com/2017/09/on-slowness-sense8-potentials-of.html

Davis, C. (2019, May 3). Perception and Conception. Retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/BxBy9_pl8uV/

Davis, C. (2019, May 15). Sylvia Martinez Invent to Learn 2019. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yMGYn2si4SI

Dewey, J. (1980). Art as experience. New York, NY: Putnam.

Google Cultural Institute. (n.d.). Fork - André Kertész - Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/fork/QQFfjm8pi5YrNA

Heybaddog. (2009, November 30). Teen Talk RARE "Math Class is Tough" Barbie! Working! Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NO0cvqT1tAE

Hrabal, B. (1976). Too Loud a Solitude. San Diego, CA: Hartcourt Brace.

Key, E. (2016). The Century of the Child. Amazon Digital Services LLC.

Lepore, J., & Lepore, J. (2018, May 31). When Barbie Went to War with Bratz. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/22/when-barbie-went-to-war-with-bratz

Maheshwari, S. (2018, April 09). YouTube Is Improperly Collecting Children's Data, Consumer Groups Say. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/09/business/media/youtube-kids-ftc-complaint.html

Martinez, S. L., & Stager, G. (2019). Invent to learn: Making, tinkering, and engineering in the classroom. S.l.: Constructing Modern Knowledge.

Metz, R., & Metz, R. (2018, February 14). Facebook's app for kids should freak parents out. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/s/609723/facebooks-app-for-kids-should-freak-parents-out/

MOMA. (2012). MoMA | Century of the Child. Retrieved from https://wayback.archive-it.org/4387/20140301000501/http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/centuryofthechild/#/

Orphanides, K. (2018, March 23). Children's YouTube is still churning out blood, suicide and cannibalism. Retrieved from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/youtube-for-kids-videos-problems-algorithm-recommend

Parrish, S. (2019, May). Decoding Difficult Conversations: My Interview with Negotiation Expert, Sheila Heen [The Knowledge Project Ep. #57]. Retrieved from https://fs.blog/sheila-heen/

Perez, S., & Perez, S. (2019, February 27). FTC ruling sees Musical.ly (TikTok) fined $5.7M for violating children's privacy law, app updated with age gate – TechCrunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/27/musical-ly-tiktok-fined-5-7m-by-ftc-for-violating-childrens-privacy-laws-will-update-app-with-age-gate/

Pinker, S. (2019). The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature. New York: Penguin.

Primero Noticias. (2019, February 21). Desfile del Carnaval de los Niños, este domingo 24 de febrero, a las 11 de la mañana. Retrieved from https://primeronoticias.com.co/2019/02/21/desfile-del-carnaval-de-los-ninos-este-domingo-24-de-febrero-a-las-11-de-la-manana/

Re, L. (2013, February 28). Talking Barbie: Math Class is Tough! Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFh8WS0s8UQ

Sontag, S. (2014). On Photography. London: Penguin Classics.

Trachtenberg, A., & amp; Meyers, A. W. (2005). Classic essays on photography. New Haven: Leetes Island Books.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotskij, L. S., & Cole, M. (1981). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press.

Weston, E. (1930, Fall). Pepper. Retrieved from https://www.artic.edu/artworks/120846/pepper?artist_ids=Edward Weston

Wikipedia. (2019, May 02). Alfred Stieglitz. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Stieglitz

Wu, K., & Zhu, J. (2018, August 08). China's Bytedance seeks to raise $3 bln at up to $75 bln valuation... Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/bytedance-fundraising/chinas-bytedance-seeks-to-raise-3-bln-at-up-to-75-bln-valuation-sources-idUSL5N1UZ0C3

Zhang, M. (2017, August 16). This Famous Pepper Photo by Edward Weston Was a 4hr Exposure at f/240. Retrieved from https://petapixel.com/2017/08/15/famous-pepper-photo-edward-weston-4hr-exposure-f240/