This post is an adaptation of a discussion between Carol Lemieux, Austin Levinson, Diego Lopez, and Chris Davis after viewing "The City of Reggio: The Boys City" for an online course - Making Learning Visible.

Group Work, Group Learning

Their city began as a cooperation as they worked in a visually linear fashion to construct the city, their common goal. Each boy specialized in a part of the city, appropriating the cognitive tool to each aesthetic need. Giacomo, the connector, worked on roads “because cities need roads so no one can get lost”. Simone, the systems thinker, designed the railroad system, perhaps thinking beyond their “city of the world”, connecting it to other cities, or working out the complexities of getting around their city. Emiliano, the congregator, emphasized squares since “the people would need a place to go and be together.” Each student working off of a special interest or strength enriches the work experience and moves it from a cooperative to a collaborative project. Each boy becomes both teacher and learner and their system of three becomes more intelligent and capable of more complex problem solving because of this diversity of skill. Like radical collaboration in a Design Thinking approach, the more diverse set of heads around the problem, the wider the scope of potential solutions.

To test their city, the three invented a system by taking turns to trace the streets of their city to make sure “it worked” and that it would not be possible to get lost. After testing the prototype and giving feedback they decided that it was ready. It may be important that this test was not imposed upon them. They chose their own measure and agreed by consensus that is was a workable city. Is it fair to say that the more collaborative work is, the more voice and choice is involved, the higher the intrinsic motivation will be?

Learning Assumptions Challenged

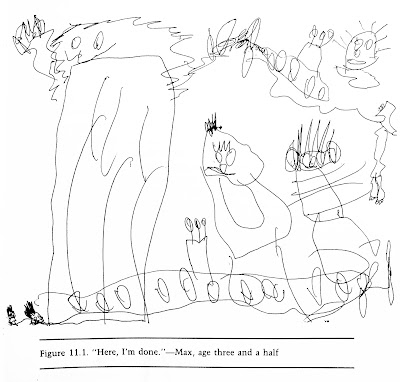

Giacomo did not engage in the activity at first. Even after the two boys extended a roadway in his direction, an invitation to “connect”, it took a direct verbal confrontation before Giacomo exposed his thought, “Cities have to work and I have to make sure this one is working.” The motivation to engage for Giacomo was an aesthetic one as he observed and calculated if this project was one that warranted his effort. Then as each boy specialized and appropriated the activity, aesthetics again played a part. Just like Max and Molly in Gardner’s study of how children appropriate drawing for their own narrative needs, the city became a connection between three different aesthetic needs - Giacomo to connect and ensure no one gets lost, Emiliano to congregate people in squares, and Simone to explore alternative modes of transport.

Aesthetic, Ethical, Affective Connection

This challenges two assumptions in teaching and learning. One, that learning is a cognitive experience as opposed to aesthetic, ethical, and affective. Giacomo was not motivated until he made an emotional and ethical connection to the project, “Cities have to work.” Emiliano worked from the strong feeling that people need a means of getting together, and Simone aesthetically elaborated on transport. It was not a matter of the right cognitive stimulation from the teacher, but allowing the space for the motivation to come from within.

Scenes from Mrs. Natasha's fifth grade Fantastic Voyage #pblchat #dtk12chat #sketchnotes visible thinking #edchat pic.twitter.com/sB2ZPha2Od

— Chris Davis (@chrisdaviscng) March 10, 2015

Looking at this example from Natasha Peterson’s fifth grade class, Anonymous V had previously researched the human body immune system, but it was in the storyboard process that her aesthetic connection to the content leveraged her drive to seek out websites and videos and to write pages and of notes complete with color coded note cards for different types of white blood cells. Up to that point Anonymous V went through immersion by browsing images in books, had a driving question to frame her study, was guided through rubrics to ensure a measurable level of content was reached, had interviewed a local doctor, and had a collaborative group to give and get feedback from. But what was holding her back up to that point? Why did she go on to explore the immune system’s complexities of monocytes, lymphocytes, metropolis, basophils, and eosinophils?

When asked, Anonymous V says she just wanted to make “a really cool video project”. So there is the leverage of the simulation, and the motivation of performing in front of her learning community for their “Spotlight Presentation”, but I believe at the heart of this motivation is the aesthetic connection she made to the content. Once she realized that her storyboard wasn’t going to make much sense unless she knew more, the visibility of her thinking was exposed, the need to know established, an intrinsic motivation tapped. The collaboration in her group at times fell apart and they did their research independently but during group critiques, a kind of healthy competition had developed as they each took pride in showing off the rich resources discovered, the new facts revealed. The group became a testing ground for new concepts and information which threaded into a collective fantasy narrative in their “Fantastic Voyage”. (see upcoming post on simulations)

Process and Outcomes

Another assumption challenged is that learning is primarily concerned with outcomes. The “soft skills” of collaboration and problem solving and working out how a group works are the real learning objectives here. If the teacher was only concerned with product the assignment may have been assessed from a checklist of what city elements are present. Then the richness of allowing each individual aesthetic and ethical strength may not have surfaced. Giacomo’s waiting for the right motivational moment would not have been accounted for. For Anonymous V, going back and forth between researching content and storyboard and movie making simulations caused her to questions and push her knowledge, while creating a sense of aesthetics around the learning.

If learning were a mere cognitive experience, a behavior psychologist’s dream, then the problems around learning center around correct stimulus, reward, and punishment. Our thoughts gravitated to the problem of the parameters placed around learning and what that says about our own concept of learning and motivation. We noticed that in this learning narrative the boys were able to choose the size paper to work on, already setting an objective for how elaborate their city would get. We chose this as a metaphor in our discussion around who designs the learning?

The problem of rubrics is not so much in the design but in their priority as primary tool within the learner’s toolkit - they are often the first thing a student sees when beginning a project. Within many rubrics, the parameters are already set and students are quickly trained to a system in which they fulfill rubric requirements. We all have to work within a school architecture with its own "rubrics of requirement", but how might we create spandrels in the spaces of creativity, how might rubrics and measurements guide but not constrain? We discussed the co-creation of rubrics using models from outside and from inside the class, where students construct the parameters. If the three boys had worked from a checklist of city elements, they may have missed the collaborative improvisations, would have gone no further than the checklist, would have missed the intrinsic aesthetic connection to their work, and would most likely have produced a product identical to every other group in the class. If Anonymous V's storyboard, screencast simulation, and final movie had all been designed with a checklist of content, then that is exactly what she and her group would have produced, a product easily assessed with that same checklist. That, we decided is a litmus test for learning design, if your students on a consistent basis produce identical products then the design may be flawed in that there is no space to go beyond, no opportunity for a deep aesthetic, ethical, and affective connection to leverage learning.

Our problem is knowing this and agreeing on this, but understanding our own parameters within a school design. Will spandrels fulfill student need and our own aesthetic, ethical, affective teaching needs, or will we find the right lever to move a pillar in the architecture. (We also notice that as we move from “safe” conversation, we tend to get metaphorical)

Where we did not quite agree was on how collaborative learning environments evolve and we struggled with nature and nurture themes of development. Two of us have spent more time in early childhood and two of us more time in upper elementary. The UE members idealized early development based on observations of spontaneous play on the playground and pushed that collaboration happens naturally with minimal guidance at early ages, the Rousseauian notion that school teaches students a system where collaborative learning process and product are not valued.

The EC members offered that collaboration is a scaffolded teaching process. Both sides agreed that the beauty of the three boys’ project was the process in motivation and in honoring the appropriation of the city to the aesthetic needs of each, while at the same time honoring the common end goal.

The EC members offered that collaboration is a scaffolded teaching process. Both sides agreed that the beauty of the three boys’ project was the process in motivation and in honoring the appropriation of the city to the aesthetic needs of each, while at the same time honoring the common end goal.

Bibliography

Anderson, A., Thies, R., & Davis, C. (2014, April 22). Let Dreams Be: Ubuntu Poem by CNG Fourth Graders. Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnEUvZDJtGU

Cruz, C. (2015, February 25). Dr. Cruz Interview on Body Systems with CNG Elementary Students. Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4NGLqe5HLQY

Davis, C., & G, A. (2015, March 4). Dr smalls plan of attack. Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlq6IW7PV3I

Démoré, E. (n.d.). @chrisdaviscng @elemprojects What a journey! Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://twitter.com/EricDemore/status/578404920254033920

Gardner, H. (1982). Art, mind, and brain: A cognitive approach to creativity. New York: Basic Books.

Krechevsky, M., & Stork, J. (2000). Challenging Educational Assumptions: Lessons from an Italian-American collaboration. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(1), 57-74. Retrieved June 7, 2015, from http://www.makinglearningvisibleresources.org/downloadable-articles.html

L. Gandini (2009) “Fundamentals of the Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education.” from http://www.education.com/reference/article/Ref_Fundamentals/

The Bootcamp Bootleg. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6, 2015, from http://dschool.stanford.edu/use-our-methods/the-bootcamp-bootleg/

The City of Reggio - The Boys' City. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kw8jeeYl2Pc

V, A., & Davis, C. (2015, May 28). Leveraging Learning with Simulation. Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FGZFNp9Ov-4

R, A., V, A., Vic, A., Isa, A., & Davis, C. (2015, March 21). Myth Busting the Immune System. Retrieved June 6, 2015, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kv8oW7urGU